A recent USA Today article asked the question “Is math education racist?”. The backlash was swift and predictable. A synecdoche of the entire debate surrounding critical race theory and minor institutional efforts to do anti-racism praxis. What should be an important conversation about pedagogy and how to best serve children from underserved backgrounds became a shouting match between those who find superiority in their ignorance and those who would rather generate views than effectively communicate.

Most people have a limited understanding of pedagogy, that is, the theory of education. In the popular imagination, being a good teacher means knowing a subject well and impartially depositing information in the minds of students. Anyone who’s been a teacher knows this is far from the truth. The ability to educate a class of children from different backgrounds, talents, and who learn in different ways, depends not on one's mastery of subject and retention of information but on their capacity to intellectually activate the kids in their classroom. It’s this fundamental truth of teaching that has prompted educators over the last few decades to interrogate the traditional pedagogical models and seek new ways of teaching in hopes of closing America’s racial education gap.

There is nothing new under the sun

In December of 1996, the Oakland School Board passed a resolution recognizing Ebonics as a legitimate language and that “African Language Systems” are genetically based and not a dialect of English. The purpose of this resolution was to facilitate using Ebonics, or African American Vernacular English (AAVE), as a bridge language. Instead of correcting kids who spoke in AAVE, teachers were to treat students as if they were in an ESL program, where a speaker's native language was used to gradually teach them how to effectively use standard English.

Unsurprisingly. controversy followed when the resolution was published by San Francisco Chronicle the following year. A large amount of the blowback landed on the phrase “genetically based”. People naturally took that to mean that educators believed the cultural product of an (assumed) deficient language was genetically tied to Black people. Not only were radical liberal teachers codifying the idea that there were genetic differences between races but also that Black people were naturally inferior such as it was difficult for them to understand objectively correct English.

In linguistics, the term “genetically based” has nothing to do with biology. Rather it refers to the relationships that languages share with each other. Some believed that the school board made a mistake in referring to AAVE as a separate language from English instead of a dialectic of English. Even those who were sympathetic to the school board's plans believed this was the result of overzealousness and a loose understanding of the linguistic principles they were leaning on. In reality the school board’s choice to call Ebonics a separate language was rooted in a long-running debate between linguists as to the origins of AAVE. Specifically, whether it evolved from enslaved peoples' attempts to communicate in a language it was forbidden for them to learn or whether it evolved from existing West African pidgin languages.

None of this nuance was able to break through to the debate, however, as the national media was more interested in stoking the flames of culture war. Most of the space was taken up by reactionary conservative vitriol and the protestations of upper and middle-class Black voices afraid of perpetuating the notion that Black kids were naturally unable to navigate the meritocracy. Stanford University linguistics professor John R. Rickford was a supporter of the Oakland School Board resolution, he described the atmosphere in a piece published by the linguistics journal Language in Society two years later:

“For instance, although the New York Times published several editorials and Op-Ed pieces critical either of Ebonics or the Oakland resolutions, linguists' attempts to get them to present a different viewpoint were all unsuccessful. I know of at least four Op-Ed submissions which they summarily rejected (by Salikoko Mufwene, by Geoffrey Pullum, by Gene Searchinger, and myself), and there were undoubtedly others. Similarly, other linguists (like Geneva Smitherman) had experiences similar to mine, in which leading television stations would do one and two hour interviews with us on the Ebonics issue, but never use any of it in their broadcasts. Linguists should not avoid these leading media sources, but be aware that breaking into them can be difficult if the views you represent do not correspond to the mainstream view. In matters of language, they often do not.”

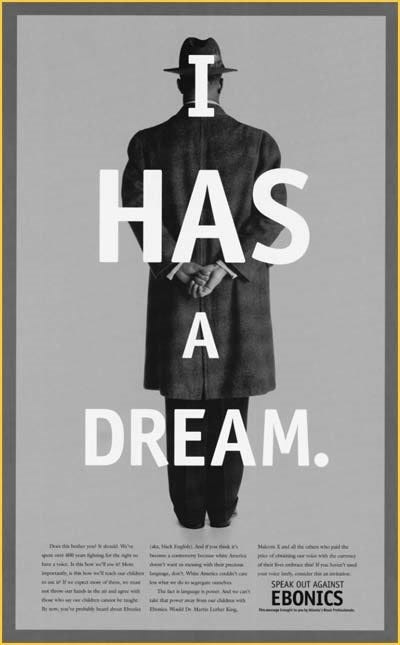

The ’90s and early aughts were a very different time from today, especially within what was thought of as liberal discourse. Four years before the Oakland School Board resolution, Bill Clinton had his “Sista Souljah moment”. Eight years after the controversy, Bill Cosby would deliver his infamous “Pound Cake” speech. At the height of the Ebonics controversy, the National Head Start Association lent its name and blessing to this ad ran in the New York Times:

The NHSA would go on to retract their endorsement of the ad but not only did the NYT run it for free, it also won an award from the Newspaper Association of America.

Everything old is new again

The current controversy over CRT and specifically racist math isn’t an exact replica of the Ebonics controversy 30 years ago. For one thing, liberal media is much more sympathetic to the idea of white supremacy and structural disadvantage. Liberal celebrities are far less likely to criticize these efforts in the same way people like Jesse Jackson and Maya Angelou criticized the Oakland School Board in the ’90s. However, the reactionary backlash is a meticulously detailed replica.

Critics are lamenting the politicization of what should be ideology-free education. What could be more independent of politics than math? One plus one equals two no matter who your parents are. The fear projected by pundits and absorbed by parents is that schools will give up trying to teach Black kids basic arithmetic and opt to assuage embarrassment over mathematical ineptitude, leaving kids unprepared to function in a society ruled by cold hard logic and arithmetic.

This fits an old familiar conservative theme. The overly permissive liberal left contributes to the degradation of society by valuing people's emotions over objective truth. But as always, the truth is much more complicated than can fit in the limited conservative imagination. Much like with Oakland School Board, schools attempting to teach math the anti-racist way are not giving up on teaching math to Black kids. What is derisively described as "woke math" is really just the attempt to develop new pedagogies that take into account the material experiences of Black children in underserved communities. They are not questioning whether it’s important to learn math, they are questioning whether the hegemonic methods of teaching and evaluating math skills are sufficient to engage children coming from non-hegemonic backgrounds.

There can be a good-faith debate on whether things like perfectionism, individual proficiency, sequential presentation of mathematical concepts, and rigid academic tracks are necessary to teaching math to students. But the idea that schools want to reinvent arithmetic and create a substandard version for underachieving minorities is nothing but a disingenuous McGuffin meant to demonize deviation from the norm.

The messenger, not the message

The proponents of counter-hegemonic pedagogy find hurdles not in an overtly antagonistic press and pop culture, but in its adherents' inability to escape the academic milieu in which these strategies were developed and communicate them to skeptical parents. Not to mention a media more obsessed with generating clicks rather than delivering information.

It's for this reason that most of the arguments we hear in favor of adaptive teaching methods center around concepts like “dismantling white supremacy” and “interrogating privilege”. Educators want to “decolonize the classroom” and be “antiracist educators with accountability”.

This is not to say that these are inherently unworthy goals, but a more effective strategy to countering reactionary backlash would be to actually explain how what they are doing is helping kids learn math. Then provide the proof of it working. The proponents of anti-racist education can better prove the deficiencies in traditional academic practices like showing your work by literally showing their work. There is an ever-growing body of pedagogical research suggesting that traditional models of education are insufficient to meet the needs of low-income and marginalized students.

Perhaps more important than showing the promise of alternative pedagogies, the educators and academics advocating for a more inclusive classroom should stop framing their efforts as against “whiteness”. “Whiteness” as an academic concept is nuanced and can be helpful in describing the social forces contributing to marginalization. As a political argument meant to build consensus, it sucks. Similarly to alternative culture based pedagogies, there is also empirical research pointing to a more effective way to build support for anti-racist efforts.

One can look to the work of political strategist Heather McGhee and historian Ian Haney Lopez, who have begun to build an empirical case for a race/class fusionist message. That is, framing matters of racial justice not as antagonistic to whiteness (which is typically assumed to mean white people) but as part of serving common class based interests that also benefit white people. As it pertains to pedagogy, it would be extremely helpful to note that alongside race based adjustments to traditional standards of learning, class based considerations are just as beneficial for white kids struggling to learn.

Ironically, in their attempts to adapt their curriculum for those who aren’t culturally compatible with traditional methods, academics neglected to adapt their message for people who aren’t culturally compatible with counter-hegemonic theory.

Attention, both positive and negative, is the most coveted currency. The ability to build consensus by reaching people where they are is at best an afterthought, and at worse viewed as acquiescing to racism. However, the blame for this cursed state of affairs should not be equally distributed. For as much as the right fetishizes logic, the reactionary mind is often inoculated against evidence disproving the basis for its indignation. No matter how you explain it, some people will never accept the counter-hegemonic position.

The simple fact is that the right is weaponizing the backlash to these kinds of deviations from the pedagogical norm to win elections. The stakes are much larger than getting ratioed for a post. This fight isn’t just about providing kids with a better learning environment, although it would still be worth fighting if it was. It’s also about the ability of democrats to build and maintain local political power. It’s something that movement conservatism has long understood, school board elections can be more important than presidential elections. Liberals do not need to nor should they abandon the cause of addressing systemic inequities, especially within education. But they do need to be much more strategic in how they navigate the politics of this effort.

There is real evidence that these new kinds of pedagogy, in concert with other poverty alleviating strategies, can help kids from underserved backgrounds close the education gap. Far from abandoning the meritocratic ideal held by conservatives, these new pedagogical methods are better preparing children from marginalized backgrounds to succeed. But as customary with culture war, the material realities of people's lives are ignored in favor of asserting moral dominance. This debate is more intent on weaponizing spectacle than actually helping kids learn.

Solidarity Forever.

Wake Up all you teachers, time to teach a new way. Maybe then they'll listen to what you have to say.